Interview with Valter Darbe

BIFA 2021 Best New Talent, “I Was My Husband”

Q: Tell us a bit about your background? How did you discover your love for photography?

At 13, assisting my cousin in the darkroom, I was fascinated by black and white printing. Even today I print my black and white photographs on silver salt paper, even when I shoot digitally, doing negatives from the files. I believe one of my characteristic features is the care of the complete cycle of production of the image from the shot to the final print, which I create with special techniques on silver salt paper (even digitally) to obtain unique and unrepeatable copies for galleries and collectors.

I graduated in photography and worked in the fields of industrial photography, still life and fashion. At university I graduated in science and technology of printing, as a natural growth path to ensure the quality of the entire process from the shot to the printed page in a newspaper. I worked in the printing industry sector for many years, but I have kept my passion for photography alive by studying the great photographers and the classics of painting. So, while I was working, I developed photographic research projects. Some of these also had a good success internationally in the 90s, especially the one on visual archetypes (entitled Hic et Nunc), which was exhibited at the Vevey International Festival de la Photographie with Jean Loup Sieff. Later I developed a research work entitled Stimmung (a German term meaning “states of mind”) which found its natural conclusion in the illustration of a book made by a group of psychotherapists and related on the new interpretation of dreams. The discovery of digital photography since 2015, has opened up new perspectives for me with a more documentary and social imprint, making me again an enthusiastic lover of photography.

Q: What was your last work and how did the initial spark of inspiration come about?

The latest work was born shortly before the pandemic and is autobiographical, focused on self-portrait and on “seeing oneself” intended as a path of identity exploration, even if I use this approach as method for portraiture too. I believe that for me it represents a significant turning point, because for my interests in the documentary and portrait genres, the relationship with the subjects is a fundamental aspect. This relationship is not possible without a consciousness (also visual) of oneself, which arises from the awareness of one’s own ego (emotions, character, body, places, roots), and from the relationship with the Others. It is a journey of knowledge, discovery and relationship, which I also started to apply for producing more emotionally effective portraits based on narration rather than on a single shot.

Q: What genre of photography do you enjoy most?

There are several photographic genres that fascinate me. Certainly the documentary, the ability to tell stories and even moods is what I prefer. I am also very interested in portraiture, especially in sociological and psychological terms.

Q: You were not only awarded Non-Professional Book Photographer of the Year 2021 for your deeply insightful work, I Was My Husband, and you also won the title, Best New Talent of the Year 2021. Can you tell us more about this project and how it came to be? What was the most notable memory or aspect that you could highlight during the creation process?

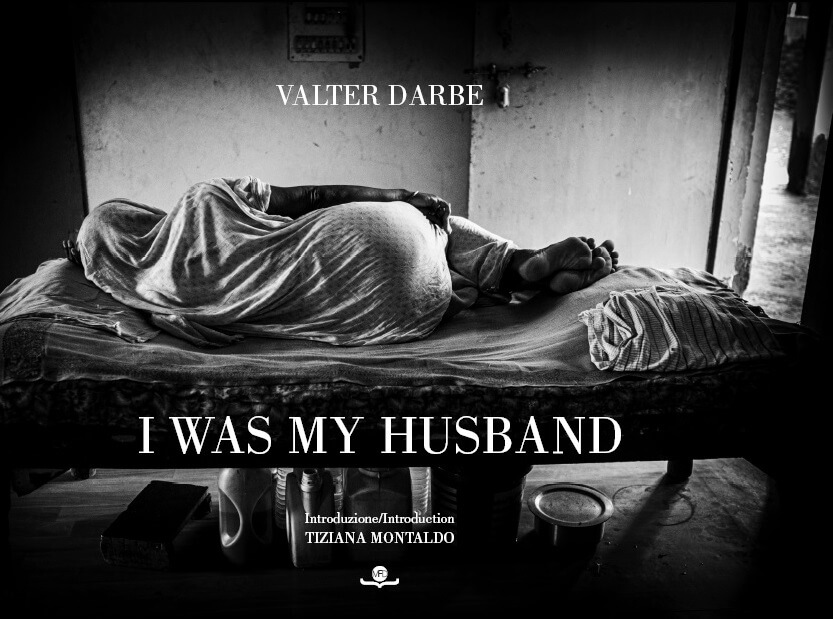

In 2015, talking about India with a human rights expert journalist (Tiziana Montaldo co-author of the texts of the book), I was asked what intrigued me about this country and what I still wanted to see. I replied that I would like to understand the social and cultural aspects of the Indian widow issue that I had heard about on some of my travels. We have invested months to collect document, to study deeply and obtain permits from the state authorities to access the public and private facilities where these women are welcomed. We found an interpreter who knew well this reality and who allowed us to meet people whose life is dedicated to the cause for the rights of these women. This allowed us to get into these structures for the first time, document and testify, also through countless interviews, the lives of these people and their stories.

From the beginning, the things that struck me most during the creation process were three:

– The sense of acceptance about their condition. I did not find anger, fear, but desolate resignation

– The joy and gratitude in finding someone – albeit a stranger – who took care of their lives, their stories, who listened to them attentively

– The signs of psychological, social and emotional annihilation perpetrated for years and which finds in each of them the signs in the white tunics, in the shaved hair, in the absence of any material good and memory. What we see of them is what they have.

Q: What does winning this award mean to you?

It is a great satisfaction that encourages me to continue studying and researching, that invites me to commit myself more and more in using photography as a means of understanding and learning

Q: What would be your dream project in photography if there would be no budget limits and you could travel anywhere, photograph anything/anyone?

I would like to develop the project I started with I Was my Husband, on the condition of women in societies characterized by a strong religious imprint. Everywhere in the world, regardless of faith, where society and culture are characterized by a strong theological imprint, women are penalized by social disparities and in the recognition of their rights. Documentation and photographic exploration can aspire to open a discussion on these issues. I was my husband is the first chapter of this investigation process.

Q: What is the one piece of advice that you received in the past about photography that you follow to this day?

Whether it’s a reportage or a portrait, trying to identify with and remain curious is a way to relate to one’s own and others’ emotions and give them an image.

Q: Are you working on something new right now? Can you tell us a little bit about it?

In this period of lockdown in which it is difficult to travel, I prefer to cultivate the portrait genre and carry out a long-term project entitled “The Gecko”, a story in which hands are the protagonists and witnesses of a journey through aging and degeneration. due to the illness of a person over 90, who perceives his existence more and more as a journey backwards made up of visions of a past life, distant memories, voices, alternating with moments of clarity and strength, to which she clings in order not to fall definitely, like a gecko on the ceiling.

“The Gecko” consistently with what was done with I Was my Husband, deals with the social marginality of fragile subjects (elderly women) in which the transformation of a elder woman is documented from being strong and autonomous, she becomes fearful and dependent on others due to old age and diseases, whose hands represent what allows her to cling to life and to keep hope, as the gecko sticks to any surface to avoid falling, not just to the ground, but from life to death.

I trust that a more freedom post-Covid openness will facilitate my resumption of production on emotional portraits, even if I must admit that this period of difficulties still offers and stimulate many new photographic projects and non-conventional approaches.